GREENBRIER COUNTY, W.Va. – They used to be mountaintops, these jagged, chopped up remnants of dirt, rock and trees piled along a dusty gravel road.

Then the bulldozers came to Blue Knob – and thousands of other locations in West Virginia. Before then, these flattened, carved-out bowls now littered with boulders and mounds of topsoil polluted with debris, were once a wave of rolling hills with crystal waters tumbling down rock-laden streambeds. This foreground of man-made chaotic pollution is a startling contrast to the background of the undisturbed 4,000-feet ridges and peaks of the surrounding Allegheny Highlands of West Virginia. Indeed, Blue Knob Surface Mine and others nearby are among the highest in elevation in The Mountain State.

They are also among the most destructive, according to several environmental groups.

Where reclamation was to occur decades ago, shrubs and scraggly trees with roots meandering underground looking for soil suitable for survival, sit in a bowl carved out by the giant machines. Distant ridgelines once hidden by the high knob that was here for millions of years are now visible. The absurdity of reclamation is the implication that a mountaintop can be returned to its undisturbed state post Mountaintop Removal (MTR). It’s a lie rooted in hubris.

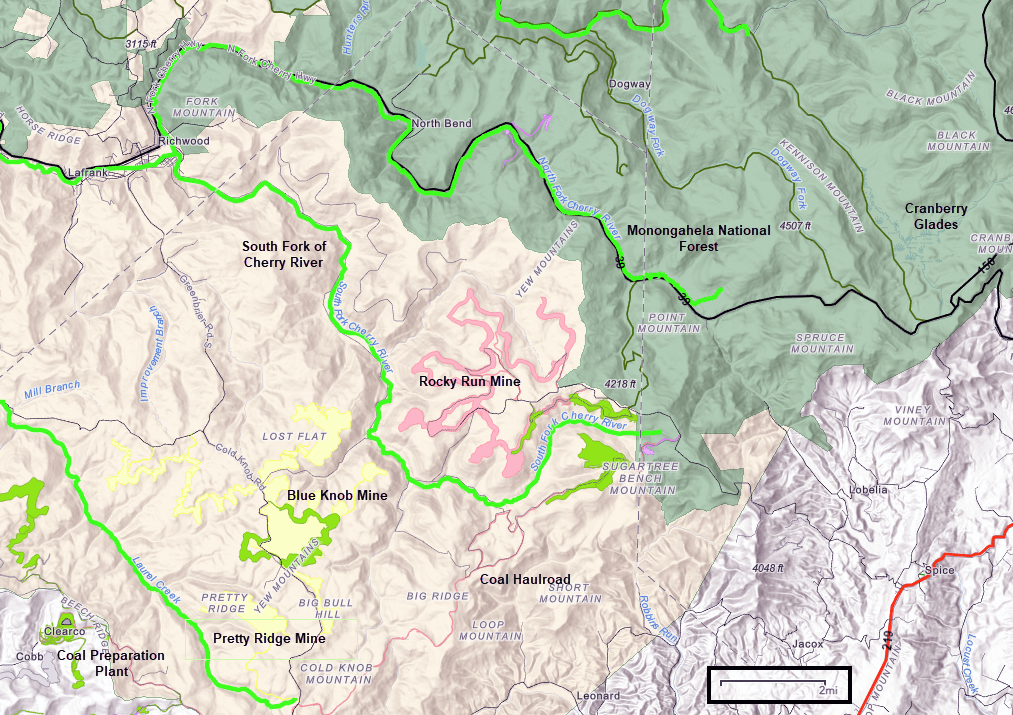

And it shouldn’t be happening. The Monongahela National Forest in eastern West Virginia is roughly 920,000 acres in size; with its Proclamation Boundary, it takes in 1.7 million acres of some of the wildest terrain in the Allegheny Highlands.

Yet, that still isn’t big enough to protect it from predatory practices of The South Fork Coal Co., LLC, owner of the Blue Knob Surface Mine, according to numerous environmental organizations. South Fork Coal is also owner of the Rocky Run Surface Mine across the ridge and nearly kissing the Forest, and more than a thousand feet above the Cranberry Glades Botanical Area. The Pretty Ridge Surface Mine straddles ridges on the opposite end of Blue Knob, and a coal haul road runs from near the South Fork of the Cherry River to Laurel Creek.

So, on April 25, the Center for Biological Diversity and four other environmental organizations – the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, Appalachian Voices, the Sierra Club and the Kanawha Forest Coalition – issued a news release stating, “Conservation groups notified the U.S. Forest Service today they intended to sue over the agency’s failure to protect endangered species from the harmful effects of coal hauling in the Monongahela National Forest.”

The statement explained, “Today’s notice asserts that the Forest Service violated the Endangered Species Act by allowing hauling of coal above the South Fork Cherry River without ensuring that it won’t harm endangered species like candy darters.” It continued, “The endangered candy darter is a small freshwater fish that lives in the South Fork Cherry River and Laurel Creek — two stronghold streams for the species. These streams are designated as critical habitat by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, meaning any harm to the streams is likely to harm the fish.”

Meg Townsend, senior freshwater attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity said, “It’s shameful that the Forest Service cut corners at the expense of endangered species like the gorgeous little candy darter. Candy darters are already on the precipice of extinction, and they can’t take any more harm from coal mining. The Forest Service needs to immediately rescind the permit allowing this disastrous coal hauling.”

Also on April 25 in a separate letter to the West Virginia Division of Mining and Reclamation, Willie Dodson, Central Appalachian Field Coordinator for Appalachian Voices wrote, “The Rocky Run Surface Mine … is situated in the headwaters of the South Fork of Cherry River, an area with exceptional and delicate natural features. The responsible management and conservation of the area is vital for maintaining biological diversity, and for the survival of the endangered candy darter. Preserving the natural splendor of the area is important to the economies of Greenbrier County, neighboring and downstream communities, and the state of West Virginia as a whole.” According to Dodson, the letter was also written on behalf of Appalachian Voices, the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, West Virginia Rivers, Coal River Mountain Watch, the Kanawha Forest Coalition, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Sierra Club West Virginia Chapter

According to Appalachian Voices, the Rocky Run Surface Mine is the primary offender, and hence the West Virginia Division of Reclamation and Mining should not allow South Fork Coal Company’s permit modification request for the Rocky Run location. In a statement, Appalachian Voices asserted, “As written, the modification … does not impose adequately strict effluent limits, monitoring requirements, or oversight and enforcement mechanisms to ensure that discharges of runoff from the Rocky Run Surface Mine will not adversely impact receiving streams. In fact, the modification would increase the likelihood of adverse impacts to receiving streams … . Therefore, the only responsible choice available to DEP in this matter is to deny the modification.”

The Blue Knob Surface Mine is hardly a model of corporate responsibility according to Appalachian Voices. “ … situated just across the South Fork of Cherry River from the Rocky Run Surface Mine, the applicant has failed to abate three Notices of Violation for a duration now exceeding 14 months. These NOVs were first issued in November 2021 for failing to backfill, regrade and vegetate disturbed areas, and for failing to properly maintain sediment structures. Since that time, the applicant has repeatedly pointed to bad weather as the justification for continually failing to correct these issues. DEP has accepted this justification, granting extension after extension to the abatement period, which remains open to this day.”

It continued, “Though South Fork Coal Company claims that it could not find a window of weather suitable to abating these environmental violations at any point since November of 2021, it is worth noting that weather conditions did not stop the company from extracting 88,000 tons of coal from the Rocky Run Surface Mine over that same period of time, according to MSHA data. This suggests that the delays in reclamation and violation abatement may have less to do with the weather and more to do with the applicant prioritizing quick revenue over regulatory compliance.”

Dodson observed, “In a region full of remarkable natural features, the headwaters of the South Fork Cherry River are particularly exceptional. It is deeply disappointing that the Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service have enabled South Fork Coal Company’s destructive practices and disregard for this special area. We are hopeful that these agencies will act quickly to address our concerns and protect the unique ecological balance of the South Fork Cherry River and the high Allegheny ridges that surround it.”

“Witnessing the highest elevation strip mine in the state, in the middle of rare red spruce forest, and so close to Cranberry Glades Botanical Area is the ultimate proof to me that nothing is sacred in this state as long as there is coal under it.”

Sierra Club’s Senior Organizing Representative Alex Cole

As the Center for Biological Diversity pointed out, “The company was already cited for violations leading to excess sedimentation in March and April 2022, a time of year when candy darters are spawning. Along with sedimentation, coal hauling could degrade the Upper Gauley watershed with coal dust from loaded coal trucks.”

Larry Thomas, president of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, responded, “The West Virginia Highlands Conservancy has a 55-year history of working in partnership with Monongahela National Forest to preserve the natural environment in the Central Appalachian Highlands, but in this case, our Forest Service partners have erred in permitting a coal haul road on National Forest land without environmental review. He continued, “The Forest Service failed to consider that converting a National Forest road to a heavy-use coal haul road would have direct environmental impacts and would also allow expansion of surface mining in a high-elevation remnant red spruce ecosystem that supports the endangered candy darter, native brook trout, and other at-risk species. We hope that the Forest Service will recognize this error and comply with the review requirements.”

The Sierra Club’s Senior Organizing Representative Alex Cole said, “Witnessing the highest elevation strip mine in the state, in the middle of rare red spruce forest, and so close to Cranberry Glades Botanical Area is the ultimate proof to me that nothing is sacred in this state as long as there is coal under it.”

© Michael M. Barrick, 2023. Mine map courtesy of Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance (ABRA). All photos credit Michael M. Barrick. Special thanks to the numerous environmental organizations that have researched this topic and provided critical information through news releases, from which these comments were collected.

[…] Environmental Groups: Strip Mines Within the Monongahela Forest Proclamation Boundary are Big Pollut… […]

[…] note: In a previous article, Environmental Groups: Strip Mines Within the Monongahela Forest Proclamation Boundary are Big Pollut…, you can learn more about the pollution caused by The South Fork Coal Co., LLC, owner of the Blue […]