March 2, 2026: Doc Watson was born 103 years ago tomorrow. I am blessed to have interviewed and met him more than once. This is offered as a tribute to his influence upon traditional Appalachian music. The article below is from an interview I had with Doc Watson that made its way into my first book, “The Hillbilly Highway” (1997). It is published below as originally written.

LENOIR, N.C. — More than three decades ago, says Doc Watson, he began playing music for one simple reason: “I had a family to support. I learned I could earn a living at it.”

Today, in his early 70s, he is still earning a living at it.

The secret of his success is apparent when the venerable folk music legend, sporting a commanding narrative voice and matter -of-fact wit, plays at cozy venues across the country.

Watson, whose musical repertoire ranges from blues to bluegrass, is perhaps best known in the 90s as the keeper of the folk music flame. He annually hosts the Merle Watson Memorial Festival in Wilkesboro, named in honor of his late son who was also a musician. The festival is one of the largest and most celebrated folk and bluegrass festivals in the nation, showcasing such traditional music icons as Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Tony Rice and David Grisman.

Though Watson’s beginnings in music were admittedly humble, it didn’t take long for fans of traditional music – in particular the acoustic sounds and then-emerging bluegrass traditions of Appalachia – to take notice. At that time, he said, he never even thought about preserving Appalachian traditions.

“I just love music and wanted to play music,” he says matter-of-factly.

Now, though, he acknowledges that others look to him as one who can be counted on to preserve – through performances and recordings – the music of the Appalachian region.

Indeed, though several so-called folk music revolutions – from the Woody Guthrie-inspired and Bob Dylan-led revival of the early ‘60s to the more recent “New Grass” revival of the mid ‘80s – Doc has remained a stable bridge to the genre’s past and present.

While saying he’s “very glad to see the tradition of acoustic music and how it’s being transformed,” Watson is not the least bit shy of sharing his opinions about what others are doing with acoustic music. “Some distort it,” he opines, but added, “Everyone has to play their own style, I reckon.”

Certainly, Watson does.

He resists being classified as a bluegrass musician. He pointed out, “Bluegrass is one segment of traditional music. It got born in the ‘40s. I play a little bluegrass. I recorded one bluegrass album, ‘The Midnight Train.’”

The offerings on that album, he says, “come from the bottom of the bluegrass totem pole.”

Watson, however, does enjoy playing the style. “We do them with a sweet modern touch, but with all the flavor left in. The rest of the music is traditional, plus whatever else I want to play.”

Despite his reluctance to be classified as a bluegrass musician, Watson said he is happy to see the commercial success bluegrass music is currently enjoying. “I’m glad it’s happening because the interest in bluegrass has spawned a big interest in good old acoustic music. That takes into consideration what I’m doing.”

Asked what has influenced him professionally, Watson responds, “Just about everyone I’ve ever listened to that I enjoyed. I started out listening to the original Carter Family. Also, Gid Tanner and The Skillet Lickers.” Other performers he singled out included Jimmie Rodgers, Chet Atkins – whom he recorded the album “Reflections” with – and even a couple of Dixieland jazz records from his youth.

“I don’t play jazz. I can’t relate to progressive jazz,” he admits. “I get lost trying to listen to it. But you name a good guitar player, and I enjoy listening.”

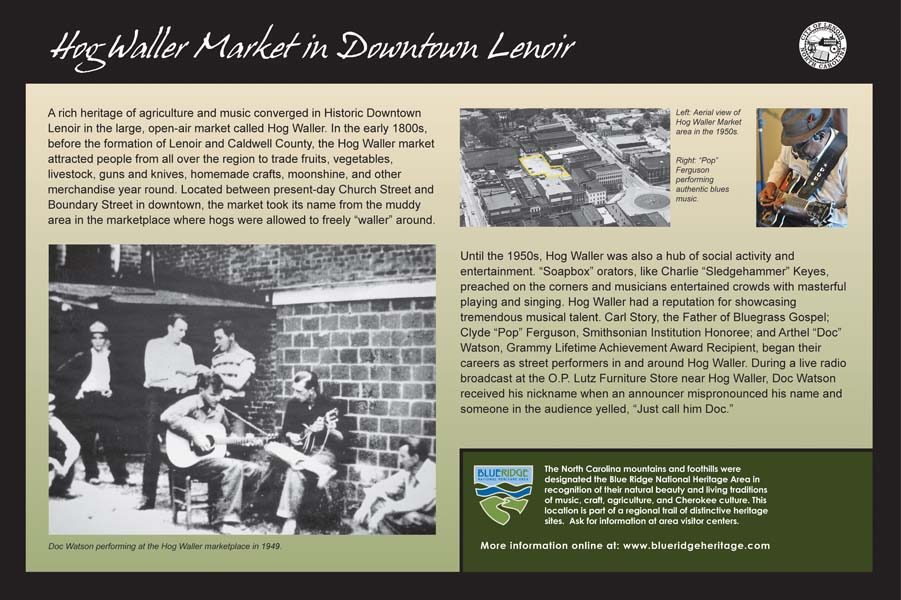

Watson, who’s first name is Arthel, got the name “Doc” in Lenoir. Someone suggested it would sound good on the radio. While that may be true, his fans probably argue that they don’t care how his name sounds, because if Doc – or Arthel – Watson is playing it, it sounds good.

Doc Watson got his professional start playing as a street performer at the Hog Waller Market in Lenoir. Lenoir, in turn, continues to play a vital role in the preservation of traditional Appalachian music. It is a must stop along the Blue Ridge Music Trails of the Blue Ridge National Heritage Area.

© Michael M. Barrick 2026.